Get Familiar: Ruff Sqwad

-

Get Familiar

-

Get Familiar

Interview by Passion Dzenga

Ruff Sqwad's story begins long before the YouTube era—back when youth clubs had vinyl decks, pirate radio ruled the city, and a TDK tape could change your week. More than twenty years ago, a loose neighbourhood posse of about thirty friends tightened into a small music unit—Slicks, Shifty Ridos and company—carrying the street name “Rough Squad” into studios, stairwells, and transmitter rooms. Their early education was communal and hands-on: Ghanaian household sounds and pop radio at home, drum & bass and garage on the block, and hours spent DJing and MCing in youth centres that doubled as classrooms. Pirate radio turned that energy outward—bedroom recordings to Deja/Rinse reach—while pressing their own vinyl taught business before there was a blueprint.

As Channel U/AKA beamed grime into living rooms, the crew condensed and professionalised, but the ethos stayed DIY: passion first, structure second. In-house producers pushed one another daily, forging a signature that’s emotional and militant at once—heard in era-defining instrumentals like “Together” and “Functions on the Low.” Two decades on, the landscape has shifted from subs to streams, yet the core hasn’t: community, craft, and the mission to move people at 140 BPM. This conversation traces that arc—from youth-club spark and pirate missions to national tours and international stages—and why, for Ruff Sqwad, the music still feels authentic.

Take us back to the very beginning—how did Rough Squad form, and who were the founding members?

It started over 20 years ago as a big neighbourhood crew—about 30 of us hanging out and moving between youth clubs. From that, a smaller music unit formed: myself, Slicks, and Shifty Ridos. We kept the larger crew’s name and carried it into the music—Rough Squad. We were about 12–13, learning as we went. Being together every day—DJing, MCing, messing with gear—turned friends into musical partners.

For readers in the Netherlands who didn’t grow up with UK youth clubs—what were they like, and why were they important?

Youth clubs were community spaces with pool tables, table tennis, and—crucially—music equipment. Many had vinyl decks or a little studio. If you had records or a way to get them, you could learn to mix; if you wrote bars, you could practise on the mic. One of my first memories is walking into Devas Youth Club, seeing a young DJ blending two drum & bass tunes so clean it sounded like one—turned out it was Dizzee Rascal. Without those clubs, a lot of us wouldn’t have developed our skills or confidence.

What sounds shaped you at home and around the ends before grime?

At home: Ghanaian music and whatever was on national radio—pop, rock, chart hits. TV introduced us to the packaging of music—boy bands, pop acts—before we discovered hip-hop, then UK sounds. In the area and at school we heard drum & bass and UK garage, which led us to grime. That mix—African/Caribbean roots, pop radio, and the UK underground—fed into our style.

When did you first ‘see yourselves’ in the music?

For some of us, drum & bass/jungle came a bit earlier; for others, UK garage into early grime was the first time we saw people who talked like us, dressed like us, and came from where we came from—So Solid, Pay As U Go, that generation. In school, loads of MCs were Afro-Caribbean; it felt natural to step in.

What did the first steps into pirate radio look like, and how did the crew name fit into that journey?

We were making tapes in bedrooms—TDKs recorded at each other’s houses—long before radio. Hearing our first track “Tings in Boots” on air (shout to Triple S Crew on Magic FM) was magical. From there, pirate was the next level. Stations had hierarchies—Rinse FM and Deja Vu had huge reach—so moving from a smaller station to Deja felt like going from a 50-cap room to 1,000 people. Rough Squad started as a street crew name; when radio came into the picture, the name was already established.

What were those early pirate missions like—logistics, crews, and risks?

We were kids travelling across London to abandoned flats or converted council spaces that hosted transmitters and studios. It could be risky—you’d hear rumours about certain areas—but the love for music outweighed it. We usually rolled five-deep at least, sometimes with non-musical friends in the entourage. Pirate radio took us out of our neighbourhoods and showed us the city.

Was there guidance from elders, or was it self-driven?

A bit of both. We were lucky: Dizzee, Wiley, DJ Target, and PAUG were from nearby, so those networks and youth clubs gave us proximity. You’d spit a lyric in a session, someone would clock you and invite you up. Early on, it was about being heard—getting a turn on the mic. When artists started getting signed, it clicked that this could change our lives.

Talk us through your first vinyl—why press it, and how did you make it happen?

“Tings in Boots” had heat on the underground—especially with a young Tinchey Strider on vocals—so pressing it felt obvious. The model was clear from our peers: build a tune in the underground, get it on radio, cut dubplates, then press. We handled everything: booking studios, getting mixes, cutting dubs for radio, then pressing vinyl and hand-to-handing to shops. Some shops said no (and later those tracks became some of our biggest). Vinyl sales became our first legit income stream before proper shows and bookings scaled.

How did distribution evolve once demand grew?

At first, it was literally records in a car, shop to shop. As demand picked up, distributors stepped in to place stock across the country. It turned DIY hustle into a small business and taught us about the industry—production costs, timelines, margins—while keeping the streets involved.

Looking back, what did that ecosystem—youth clubs, pirates, vinyl—give Rough Squad that streaming can’t?

Access and identity. Youth clubs gave us skills and community. Pirate radio gave us reach, urgency, and a live feedback loop. Vinyl gave us ownership and revenue. Together, they made a pathway for kids from our ends to be heard—before algorithms—by sheer force of sound and consistency.

Channel U/AKA put you on TV screens. How did that shift—from pirate sets and vinyl—change things?

It condensed the crew. We started as 30 friends on the road, became 6–7 for the pirate era, and tightened further once TV rotation kicked in. When one of us started smashing shows nationwide with a bigger camp and then signed a deal, the spotlight widened. It felt strange at first—seeing your guy on other stations while you’re still doing your own sets—but it made sense and lifted the whole name. Tours followed, some of us jumped on those dates, and suddenly we’d gone from radio rooms to arenas of 10–15k.

Mid-2000s grime went entrepreneurial—DVDs, tees, CDs, Star in the Hood, as well as exposure on commercial radio such as BBC Radio 1Xtra and Kiss FM. How did you keep the engine running as you moved from teens to young adults?

Passion first, then structure. We lived together musically—woke up making tunes, passed houses to listen, hit radio twice a week, booked studio, pressed records. It wasn’t Google Calendars; it was brotherhood. Roles emerged: some of us organised sessions, deadlines and drops; others handled mixes, vinyl, videos. Because we were around each other 24/7, decisions happened in motion.

“Together” still erupts clubs. What’s the origin story?

Dirty Danger made the beat at around 14. It began as a loop—open, musical, cinematic. The moment it came through the wall, it felt special. He nearly binned it; we pushed him to finish it. In a later studio run (he funded the time), the hook got laid and the tune became a crew staple. It’s the clarity and space that let everyone paint emotion—that’s why it lasts.

And “Functions on the Low”? How did that sound crystallise?

Nothing was board-roomed. We had multiple in-house producers (each with a distinct palette) feeding off one another—same DAWs, different ears. Friendly pressure kept the bar high: if someone dropped four new riddims today, you weren’t showing up empty-handed tomorrow. We’d build a tune in a week to test it on radio the next. The overlap wasn’t formula; it was shared standards and constant iteration.

Quality control in a big crew is tricky. How did you keep the sound coherent without boxing yourselves in?

By listening—to each other and to the crowd. It wasn’t competition so much as catalysts: one synth line would spark another tune; a drum pocket would trigger a new flip. Because the workflow was relentless—five ideas a day at times—the weak fell away and the strongest ideas defined “the sound” organically.

What’s changed in grime across 20+ years—and what hasn’t?

DIY radio is gone, streaming is king, labels and platforms shifted the power a few times. But the culture cycles back: collaboration is up, the community feel is returning, and people are making grime because it moves them, not just the metrics. It doesn’t feel like 20 years because we never stopped.

Grime’s international pull is real. Why keep bringing the sound to places like the Netherlands?

Because the sound is bigger than us. It sits around 140 BPM, but it’s its own lane—recognisable, iconic, still evolving. We’re grateful to travel with it and rebuild, city by city. The Netherlands has long supported UK bass culture, and linking with local pillars only strengthens the ecosystem.

If your music lived in a film, what genre would it score?

Epic battle cinema—think 300 or Gladiator. Melodic, martial, high-stakes energy. It’s war music.

On Saturday, November 1st, La Cassette take over MONO, Rotterdam presenting a crewnight. Bridging the gap between the Netherlands and the UK. Tickets are available now with party contributions starting at €14 and going up to €17.50.

Related Articles

-

Interview by Passion DzengaRuff Sqwad's story begins long before the YouTube era—back when youth clubs had vinyl decks, pirate radio ruled the city, and a TDK tape could change your week. More than twenty years ago, a loose neighbourhood posse of about thirty friends tightened into a small music unit—Slicks, Shifty Ridos and company—carrying the street name “Rough Squad” into studios, stairwells, and transmitter rooms. Their early education was communal and hands-on: Ghanaian household sounds and pop radio at home, drum & bass and garage on the block, and hours spent DJing and MCing in youth centres that doubled as classrooms. Pirate radio turned that energy outward—bedroom recordings to Deja/Rinse reach—while pressing their own vinyl taught business before there was a blueprint.As Channel U/AKA beamed grime into living rooms, the crew condensed and professionalised, but the ethos stayed DIY: passion first, structure second. In-house producers pushed one another daily, forging a signature that’s emotional and militant at once—heard in era-defining instrumentals like “Together” and “Functions on the Low.” Two decades on, the landscape has shifted from subs to streams, yet the core hasn’t: community, craft, and the mission to move people at 140 BPM. This conversation traces that arc—from youth-club spark and pirate missions to national tours and international stages—and why, for Ruff Sqwad, the music still feels authentic.Take us back to the very beginning—how did Rough Squad form, and who were the founding members?It started over 20 years ago as a big neighbourhood crew—about 30 of us hanging out and moving between youth clubs. From that, a smaller music unit formed: myself, Slicks, and Shifty Ridos. We kept the larger crew’s name and carried it into the music—Rough Squad. We were about 12–13, learning as we went. Being together every day—DJing, MCing, messing with gear—turned friends into musical partners.For readers in the Netherlands who didn’t grow up with UK youth clubs—what were they like, and why were they important?Youth clubs were community spaces with pool tables, table tennis, and—crucially—music equipment. Many had vinyl decks or a little studio. If you had records or a way to get them, you could learn to mix; if you wrote bars, you could practise on the mic. One of my first memories is walking into Devas Youth Club, seeing a young DJ blending two drum & bass tunes so clean it sounded like one—turned out it was Dizzee Rascal. Without those clubs, a lot of us wouldn’t have developed our skills or confidence.What sounds shaped you at home and around the ends before grime?At home: Ghanaian music and whatever was on national radio—pop, rock, chart hits. TV introduced us to the packaging of music—boy bands, pop acts—before we discovered hip-hop, then UK sounds. In the area and at school we heard drum & bass and UK garage, which led us to grime. That mix—African/Caribbean roots, pop radio, and the UK underground—fed into our style.When did you first ‘see yourselves’ in the music?For some of us, drum & bass/jungle came a bit earlier; for others, UK garage into early grime was the first time we saw people who talked like us, dressed like us, and came from where we came from—So Solid, Pay As U Go, that generation. In school, loads of MCs were Afro-Caribbean; it felt natural to step in.What did the first steps into pirate radio look like, and how did the crew name fit into that journey?We were making tapes in bedrooms—TDKs recorded at each other’s houses—long before radio. Hearing our first track “Tings in Boots” on air (shout to Triple S Crew on Magic FM) was magical. From there, pirate was the next level. Stations had hierarchies—Rinse FM and Deja Vu had huge reach—so moving from a smaller station to Deja felt like going from a 50-cap room to 1,000 people. Rough Squad started as a street crew name; when radio came into the picture, the name was already established.What were those early pirate missions like—logistics, crews, and risks?We were kids travelling across London to abandoned flats or converted council spaces that hosted transmitters and studios. It could be risky—you’d hear rumours about certain areas—but the love for music outweighed it. We usually rolled five-deep at least, sometimes with non-musical friends in the entourage. Pirate radio took us out of our neighbourhoods and showed us the city.Was there guidance from elders, or was it self-driven?A bit of both. We were lucky: Dizzee, Wiley, DJ Target, and PAUG were from nearby, so those networks and youth clubs gave us proximity. You’d spit a lyric in a session, someone would clock you and invite you up. Early on, it was about being heard—getting a turn on the mic. When artists started getting signed, it clicked that this could change our lives.Talk us through your first vinyl—why press it, and how did you make it happen?“Tings in Boots” had heat on the underground—especially with a young Tinchey Strider on vocals—so pressing it felt obvious. The model was clear from our peers: build a tune in the underground, get it on radio, cut dubplates, then press. We handled everything: booking studios, getting mixes, cutting dubs for radio, then pressing vinyl and hand-to-handing to shops. Some shops said no (and later those tracks became some of our biggest). Vinyl sales became our first legit income stream before proper shows and bookings scaled.How did distribution evolve once demand grew?At first, it was literally records in a car, shop to shop. As demand picked up, distributors stepped in to place stock across the country. It turned DIY hustle into a small business and taught us about the industry—production costs, timelines, margins—while keeping the streets involved.Looking back, what did that ecosystem—youth clubs, pirates, vinyl—give Rough Squad that streaming can’t?Access and identity. Youth clubs gave us skills and community. Pirate radio gave us reach, urgency, and a live feedback loop. Vinyl gave us ownership and revenue. Together, they made a pathway for kids from our ends to be heard—before algorithms—by sheer force of sound and consistency.Channel U/AKA put you on TV screens. How did that shift—from pirate sets and vinyl—change things?It condensed the crew. We started as 30 friends on the road, became 6–7 for the pirate era, and tightened further once TV rotation kicked in. When one of us started smashing shows nationwide with a bigger camp and then signed a deal, the spotlight widened. It felt strange at first—seeing your guy on other stations while you’re still doing your own sets—but it made sense and lifted the whole name. Tours followed, some of us jumped on those dates, and suddenly we’d gone from radio rooms to arenas of 10–15k.Mid-2000s grime went entrepreneurial—DVDs, tees, CDs, Star in the Hood, as well as exposure on commercial radio such as BBC Radio 1Xtra and Kiss FM. How did you keep the engine running as you moved from teens to young adults?Passion first, then structure. We lived together musically—woke up making tunes, passed houses to listen, hit radio twice a week, booked studio, pressed records. It wasn’t Google Calendars; it was brotherhood. Roles emerged: some of us organised sessions, deadlines and drops; others handled mixes, vinyl, videos. Because we were around each other 24/7, decisions happened in motion.“Together” still erupts clubs. What’s the origin story?Dirty Danger made the beat at around 14. It began as a loop—open, musical, cinematic. The moment it came through the wall, it felt special. He nearly binned it; we pushed him to finish it. In a later studio run (he funded the time), the hook got laid and the tune became a crew staple. It’s the clarity and space that let everyone paint emotion—that’s why it lasts.And “Functions on the Low”? How did that sound crystallise?Nothing was board-roomed. We had multiple in-house producers (each with a distinct palette) feeding off one another—same DAWs, different ears. Friendly pressure kept the bar high: if someone dropped four new riddims today, you weren’t showing up empty-handed tomorrow. We’d build a tune in a week to test it on radio the next. The overlap wasn’t formula; it was shared standards and constant iteration.Quality control in a big crew is tricky. How did you keep the sound coherent without boxing yourselves in?By listening—to each other and to the crowd. It wasn’t competition so much as catalysts: one synth line would spark another tune; a drum pocket would trigger a new flip. Because the workflow was relentless—five ideas a day at times—the weak fell away and the strongest ideas defined “the sound” organically.What’s changed in grime across 20+ years—and what hasn’t?DIY radio is gone, streaming is king, labels and platforms shifted the power a few times. But the culture cycles back: collaboration is up, the community feel is returning, and people are making grime because it moves them, not just the metrics. It doesn’t feel like 20 years because we never stopped.Grime’s international pull is real. Why keep bringing the sound to places like the Netherlands?Because the sound is bigger than us. It sits around 140 BPM, but it’s its own lane—recognisable, iconic, still evolving. We’re grateful to travel with it and rebuild, city by city. The Netherlands has long supported UK bass culture, and linking with local pillars only strengthens the ecosystem.If your music lived in a film, what genre would it score?Epic battle cinema—think 300 or Gladiator. Melodic, martial, high-stakes energy. It’s war music.On Saturday, November 1st, La Cassette take over MONO, Rotterdam presenting a crewnight. Bridging the gap between the Netherlands and the UK. Tickets are available now with party contributions starting at €14 and going up to €17.50.

Interview by Passion DzengaRuff Sqwad's story begins long before the YouTube era—back when youth clubs had vinyl decks, pirate radio ruled the city, and a TDK tape could change your week. More than twenty years ago, a loose neighbourhood posse of about thirty friends tightened into a small music unit—Slicks, Shifty Ridos and company—carrying the street name “Rough Squad” into studios, stairwells, and transmitter rooms. Their early education was communal and hands-on: Ghanaian household sounds and pop radio at home, drum & bass and garage on the block, and hours spent DJing and MCing in youth centres that doubled as classrooms. Pirate radio turned that energy outward—bedroom recordings to Deja/Rinse reach—while pressing their own vinyl taught business before there was a blueprint.As Channel U/AKA beamed grime into living rooms, the crew condensed and professionalised, but the ethos stayed DIY: passion first, structure second. In-house producers pushed one another daily, forging a signature that’s emotional and militant at once—heard in era-defining instrumentals like “Together” and “Functions on the Low.” Two decades on, the landscape has shifted from subs to streams, yet the core hasn’t: community, craft, and the mission to move people at 140 BPM. This conversation traces that arc—from youth-club spark and pirate missions to national tours and international stages—and why, for Ruff Sqwad, the music still feels authentic.Take us back to the very beginning—how did Rough Squad form, and who were the founding members?It started over 20 years ago as a big neighbourhood crew—about 30 of us hanging out and moving between youth clubs. From that, a smaller music unit formed: myself, Slicks, and Shifty Ridos. We kept the larger crew’s name and carried it into the music—Rough Squad. We were about 12–13, learning as we went. Being together every day—DJing, MCing, messing with gear—turned friends into musical partners.For readers in the Netherlands who didn’t grow up with UK youth clubs—what were they like, and why were they important?Youth clubs were community spaces with pool tables, table tennis, and—crucially—music equipment. Many had vinyl decks or a little studio. If you had records or a way to get them, you could learn to mix; if you wrote bars, you could practise on the mic. One of my first memories is walking into Devas Youth Club, seeing a young DJ blending two drum & bass tunes so clean it sounded like one—turned out it was Dizzee Rascal. Without those clubs, a lot of us wouldn’t have developed our skills or confidence.What sounds shaped you at home and around the ends before grime?At home: Ghanaian music and whatever was on national radio—pop, rock, chart hits. TV introduced us to the packaging of music—boy bands, pop acts—before we discovered hip-hop, then UK sounds. In the area and at school we heard drum & bass and UK garage, which led us to grime. That mix—African/Caribbean roots, pop radio, and the UK underground—fed into our style.When did you first ‘see yourselves’ in the music?For some of us, drum & bass/jungle came a bit earlier; for others, UK garage into early grime was the first time we saw people who talked like us, dressed like us, and came from where we came from—So Solid, Pay As U Go, that generation. In school, loads of MCs were Afro-Caribbean; it felt natural to step in.What did the first steps into pirate radio look like, and how did the crew name fit into that journey?We were making tapes in bedrooms—TDKs recorded at each other’s houses—long before radio. Hearing our first track “Tings in Boots” on air (shout to Triple S Crew on Magic FM) was magical. From there, pirate was the next level. Stations had hierarchies—Rinse FM and Deja Vu had huge reach—so moving from a smaller station to Deja felt like going from a 50-cap room to 1,000 people. Rough Squad started as a street crew name; when radio came into the picture, the name was already established.What were those early pirate missions like—logistics, crews, and risks?We were kids travelling across London to abandoned flats or converted council spaces that hosted transmitters and studios. It could be risky—you’d hear rumours about certain areas—but the love for music outweighed it. We usually rolled five-deep at least, sometimes with non-musical friends in the entourage. Pirate radio took us out of our neighbourhoods and showed us the city.Was there guidance from elders, or was it self-driven?A bit of both. We were lucky: Dizzee, Wiley, DJ Target, and PAUG were from nearby, so those networks and youth clubs gave us proximity. You’d spit a lyric in a session, someone would clock you and invite you up. Early on, it was about being heard—getting a turn on the mic. When artists started getting signed, it clicked that this could change our lives.Talk us through your first vinyl—why press it, and how did you make it happen?“Tings in Boots” had heat on the underground—especially with a young Tinchey Strider on vocals—so pressing it felt obvious. The model was clear from our peers: build a tune in the underground, get it on radio, cut dubplates, then press. We handled everything: booking studios, getting mixes, cutting dubs for radio, then pressing vinyl and hand-to-handing to shops. Some shops said no (and later those tracks became some of our biggest). Vinyl sales became our first legit income stream before proper shows and bookings scaled.How did distribution evolve once demand grew?At first, it was literally records in a car, shop to shop. As demand picked up, distributors stepped in to place stock across the country. It turned DIY hustle into a small business and taught us about the industry—production costs, timelines, margins—while keeping the streets involved.Looking back, what did that ecosystem—youth clubs, pirates, vinyl—give Rough Squad that streaming can’t?Access and identity. Youth clubs gave us skills and community. Pirate radio gave us reach, urgency, and a live feedback loop. Vinyl gave us ownership and revenue. Together, they made a pathway for kids from our ends to be heard—before algorithms—by sheer force of sound and consistency.Channel U/AKA put you on TV screens. How did that shift—from pirate sets and vinyl—change things?It condensed the crew. We started as 30 friends on the road, became 6–7 for the pirate era, and tightened further once TV rotation kicked in. When one of us started smashing shows nationwide with a bigger camp and then signed a deal, the spotlight widened. It felt strange at first—seeing your guy on other stations while you’re still doing your own sets—but it made sense and lifted the whole name. Tours followed, some of us jumped on those dates, and suddenly we’d gone from radio rooms to arenas of 10–15k.Mid-2000s grime went entrepreneurial—DVDs, tees, CDs, Star in the Hood, as well as exposure on commercial radio such as BBC Radio 1Xtra and Kiss FM. How did you keep the engine running as you moved from teens to young adults?Passion first, then structure. We lived together musically—woke up making tunes, passed houses to listen, hit radio twice a week, booked studio, pressed records. It wasn’t Google Calendars; it was brotherhood. Roles emerged: some of us organised sessions, deadlines and drops; others handled mixes, vinyl, videos. Because we were around each other 24/7, decisions happened in motion.“Together” still erupts clubs. What’s the origin story?Dirty Danger made the beat at around 14. It began as a loop—open, musical, cinematic. The moment it came through the wall, it felt special. He nearly binned it; we pushed him to finish it. In a later studio run (he funded the time), the hook got laid and the tune became a crew staple. It’s the clarity and space that let everyone paint emotion—that’s why it lasts.And “Functions on the Low”? How did that sound crystallise?Nothing was board-roomed. We had multiple in-house producers (each with a distinct palette) feeding off one another—same DAWs, different ears. Friendly pressure kept the bar high: if someone dropped four new riddims today, you weren’t showing up empty-handed tomorrow. We’d build a tune in a week to test it on radio the next. The overlap wasn’t formula; it was shared standards and constant iteration.Quality control in a big crew is tricky. How did you keep the sound coherent without boxing yourselves in?By listening—to each other and to the crowd. It wasn’t competition so much as catalysts: one synth line would spark another tune; a drum pocket would trigger a new flip. Because the workflow was relentless—five ideas a day at times—the weak fell away and the strongest ideas defined “the sound” organically.What’s changed in grime across 20+ years—and what hasn’t?DIY radio is gone, streaming is king, labels and platforms shifted the power a few times. But the culture cycles back: collaboration is up, the community feel is returning, and people are making grime because it moves them, not just the metrics. It doesn’t feel like 20 years because we never stopped.Grime’s international pull is real. Why keep bringing the sound to places like the Netherlands?Because the sound is bigger than us. It sits around 140 BPM, but it’s its own lane—recognisable, iconic, still evolving. We’re grateful to travel with it and rebuild, city by city. The Netherlands has long supported UK bass culture, and linking with local pillars only strengthens the ecosystem.If your music lived in a film, what genre would it score?Epic battle cinema—think 300 or Gladiator. Melodic, martial, high-stakes energy. It’s war music.On Saturday, November 1st, La Cassette take over MONO, Rotterdam presenting a crewnight. Bridging the gap between the Netherlands and the UK. Tickets are available now with party contributions starting at €14 and going up to €17.50. -

Get Familiar: Fokko Juweliers

Get Familiar: Fokko Juweliers

Interview by Passion Dzenga For our AW25 lookbook, we wanted every detail to reflect heritage, craftsmanship and modern storytelling — which is why we chose to style the collection with pieces from Fokko Juweliers. Known for their authentic Surinamese designs and deep cultural roots, Fokko doesn’t just create jewelry — they craft connection.As the largest Surinamese jewelry brand today, Fokko Juweliers is redefining what it means to wear tradition with pride. Their pieces blend ancestral craftsmanship with contemporary detail, honoring heritage while looking ahead. We caught up with the founder to get familiar with the story behind the brand — from humble beginnings on Facebook to becoming a million-euro company bridging cultures across the Netherlands and Suriname. Let’s dive in.First things first — how did Fokko Juweliers come to life? What’s the story behind the brand?After finishing my studies, I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. Together with a friend, Remi’s Juwelen — a Surinamese jeweler in Groningen — I started selling Surinamese jewelry online via platforms like Marktplaats and Facebook. We had a one-week delivery time.Over time, demand started growing, not just locally but from all over the country. At the time, Surinamese jewelry wasn’t really available online, so I decided to start my own brand: Fokko Juweliers. I didn’t want to name the business after myself directly, so I used my middle name — Fokko, named after my Dutch grandfather. That was back in 2009.As the brand grew, I launched Fokko Design in 2011: my own line of Surinamese jewelry inspired by authentic cultural pieces. Today, we ship over 10,000 orders a year, with an annual turnover of more than a million euros, and have a team of 10 people working with us.That’s an impressive journey! What are the values that drive Fokko Juweliers?At Fokko Juweliers, we’re deeply rooted in several core values that guide everything we do. Authenticity is at the heart of our work — we’re committed to preserving the traditional Surinamese culture and craftsmanship in every single piece we create. Our jewelry is a celebration of heritage, and we strive to keep that spirit alive through careful, meaningful design.Craftsmanship is equally important. Every item is created with precision, care, and an eye for detail — high quality isn’t optional; it’s a standard. We also place great value on diversity, reflecting the richness of Suriname’s multicultural society, where different ethnic influences come together in harmony. Sustainability is another pillar of our approach. We use eco-friendly materials and ethical production methods to ensure that our impact is positive, not just culturally, but environmentally as well.Connection plays a big role in our mission. We aim to connect people with Surinamese history and culture through our jewelry, and we’re proud to collaborate with Surinamese businesses — from local photographers to marketing partners. Our photos are often taken in Suriname itself, reinforcing that connection.We also feel immense pride — in our heritage, our team, and in the ability to share Surinamese stories with the world. Through our blog, we strive to raise awareness and appreciation for Suriname and its unique jewelry traditions. Finally, creativity is woven into our process. We love innovating and creating designs that respect traditional elements while incorporating a modern style.You operate in both the Netherlands and Suriname. How do the markets differ?There’s a notable difference in production methods between the two markets. In Suriname, jewelry is often handmade or crafted using basic molds, which results in pieces that may not have the polished finish expected in the Netherlands. That’s why we’ve invested heavily in advanced machinery and in training local Surinamese talent. Thanks to these investments, we’re now able to produce Surinamese jewelry that matches Dutch standards in both quality and finish. We can achieve intricate details that wouldn’t have been possible by hand alone, allowing us to blend tradition with modern precision.What makes Fokko Design stand out from other jewelry brands?What sets us apart is the authentic cultural connection embedded in each of our designs. Our jewelry tells genuine stories rooted in Surinamese traditions and customs, whereas many competing brands often create more generic, commercial pieces that lack that specific cultural background — and often, any personal connection to Suriname at all.We also work with authentic Surinamese materials and traditional techniques. For instance, we use the original hand-blown Ala Kondre beads, while others opt for cheaper Chinese replicas. This commitment to authenticity is a defining aspect of our brand. But we don’t stop there. We offer more than just products — we provide a full cultural experience. Whether it’s through our blog or sponsorship of Surinamese events, we create a space where people can engage with and feel proud of their heritage.And importantly, our jewelry remains affordable. For us, it’s not just about profit. Our mission is to tell Suriname’s story — and we want as many people as possible to be able to access and connect with it. Each piece we create reflects Suriname’s rich history, traditions, and cultural diversity, allowing our customers to wear something meaningful and proudly rooted in identity.What kind of partners or retailers do you collaborate with?When we look for partners to carry our Surinamese jewelry brand, we seek those who align with our vision and values. It’s important that they have a deep respect and appreciation for the cultural heritage behind our designs. We want to work with people who can genuinely communicate that story to their customers, because in Surinamese culture, jewelry holds significant meaning.We also prioritize quality. Our ideal partners are committed to offering their clients high-quality, handcrafted pieces — not mass-produced products. On top of that, they should be passionate about creating a strong customer experience — one that’s personal, warm, and meaningful.We value collaboration and want to work with people who are enthusiastic about growing with us. We believe our jewelry is much more than an accessory — it carries stories, memories, and identity. So, any partner we work with needs to understand what they’re offering and why it matters.And who is your typical customer?Our typical customer is someone who’s not just shopping for jewelry, but looking for something truly meaningful. They value craftsmanship and authenticity and are often drawn to the cultural and personal significance behind our pieces. These are people who want to wear or gift something that tells a story — something that resonates with their heritage, or simply stands out for its uniqueness.When they visit Fokko Juweliers, they’re looking for more than just a purchase. They want to feel welcomed, receive expert guidance, and be inspired. Our customers appreciate the personal attention we offer, as well as the passion and care we put into every single piece. It’s crucial that our team has in-depth knowledge to match each customer with something that truly suits their style, story, and wishes.In short, they’re seeking a warm, trustworthy, and authentic shopping experience where they feel heard, valued, and understood.Looking ahead — what’s next for Fokko Juweliers?We’re always looking forward and evolving based on our experience and customer feedback. While we’re proud of our current collection, we’re also excited about its future growth. In the coming months, we plan to introduce new designs that bring together Suriname’s rich cultural elements with modern trends.Another key goal is expanding our network of retail partners, especially in Belgium and eastern parts of the Netherlands, so we can share our passion with even more people. But for us, growth needs to be sustainable. Expanding too quickly can compromise quality and our close connection with customers — something we never want to lose.That’s why we take our time. We’re focused on maintaining the high standards we’ve set, both in our jewelry and in our customer service. Quality will always come before quantity for us. Sustainable growth allows us to stay true to our values and ensures that we remain a reliable, thoughtful, and personal brand long into the future.What legacy do you hope Fokko Juweliers leaves behind?We’re proud that Fokko Design has become the largest Surinamese jewelry brand — and that didn’t happen overnight. It took years of passion, hard work, and staying true to our identity. We’ve built a strong, trusted name both in Suriname and the Netherlands, and our customers see us as a reliable and inspiring brand that honors Surinamese culture and brings it to life through beautiful jewelry.Our biggest hope is to continue connecting people to Suriname’s rich traditions, and to do so with authenticity, quality, and care. We want to be remembered not just for our products, but for the stories we told, the people we inspired, and the cultural pride we shared with the world.-

Get Familiar

-

-

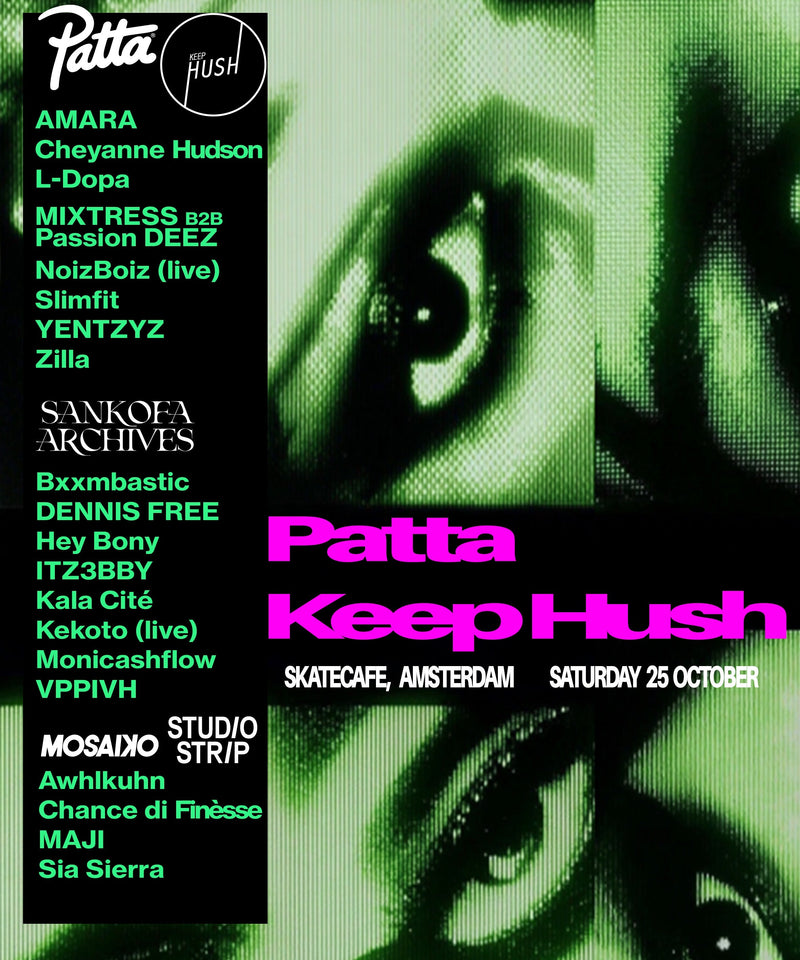

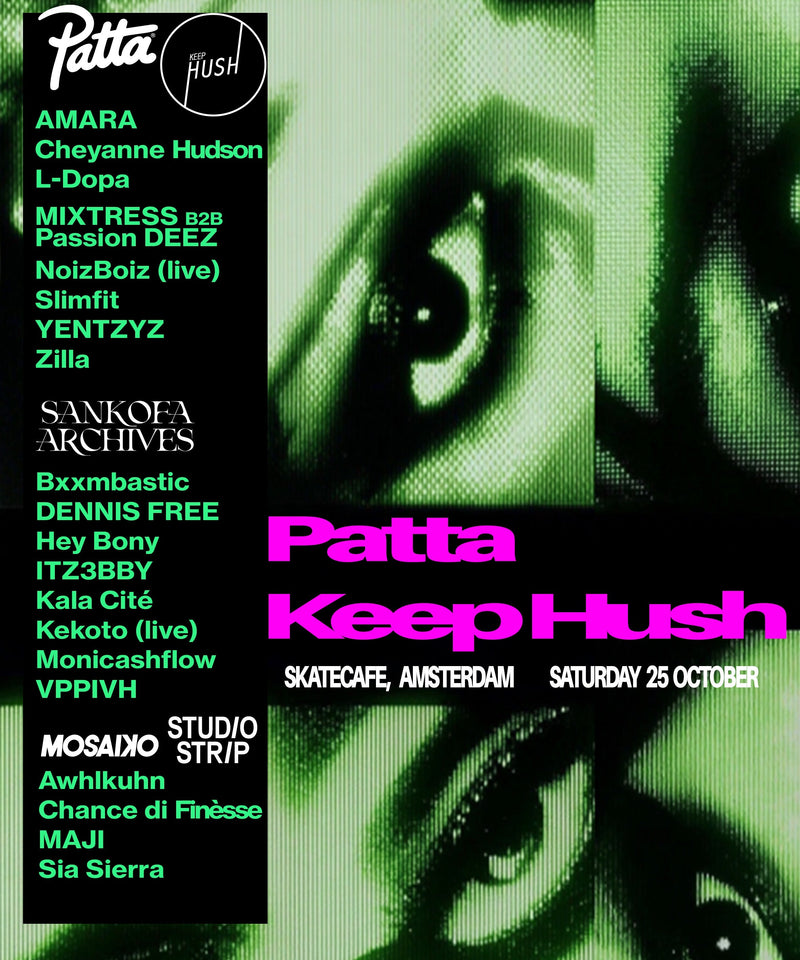

Patta x Keep Hush at Skatecafe

Patta x Keep Hush at Skatecafe

This marks the third year that Patta and Keep Hush come together — and you know what they say, three’s the magic number. So this time, we’re going bigger. We’ve called upon three of our favourite Amsterdam-based collectives — Sankofa Archives, Mosaiko and Studio Strip — to help us bring the energy higher than ever. This isn’t your average ADE rave. This is community in motion — collectives linking up, sounds colliding and people coming together to build something bigger than themselves.Patta x Keep Hush:AMARA • Cheyanne Hudson • NoizBoiz (Live) • MIXTRESS b2b Passion DEEZ • L-Dopa • Slimfit • YENTZYZ • ZillaSankofa Archives:Bxxmbastic • DENNIS FREE • Hey Bony • Itz3bby • Kekoto (Live) • Monicashflow • VPPIVH • Hosted by Kala CitéMosaiko x Studio Strip:MAJI • Chance di Finèsse • Awhlkun • Sia Sierra📍 Skatecafé, Amsterdam📆 Saturday, October 25th🎟️ Tickets are live now — don’t sleep. Join the movement and secure your spot at Patta x Keep Hush, where the community takes centre stage.-

Events

-

-

Get Familiar: NoizBoiz

Get Familiar: NoizBoiz

Interview by Passion DzengaTwo decades deep in the Dutch underground, NoizBoiz stands as living proof that grime, garage, and bass music transcend borders. Emerging from the streets of Rotterdam in the early 2000s, they fused UK-inspired 140 energy with their own Caribbean-Dutch influences — long before “international grime” was even a term. What started as teens freestyling over jungle and drum & bass beats evolved into one of the Netherlands’ most pioneering collectives, bridging local street culture, graffiti, and skate scenes with a distinctly UK sound.From DIY setups to international tours, NoizBoiz’s journey mirrors the pulse of grime itself — resourceful, raw, and endlessly adaptive. Along the way, they connected with UK heavyweights like Wiley, Skepta, and JME, culminating in collaborations that helped cement their legacy as cross-continental innovators. Through their long-running series NoizBoiz Presenteert: Zware Bassen, Zware Beats, they’ve built a platform that not only champions Dutch producers and MCs but also keeps the UK–Dutch sound system dialogue alive and evolving.Now, with over twenty years in the game, a new generation of collaborators, and their official DJ Jill-Ann joining the crew, NoizBoiz continue to evolve while staying true to their foundation — heavy beats, heavy bars, and full authenticity. Speaking from Los Angeles, Axel and Don spoke to us ahead of their upcoming Patta x Keep Hush performance and new project drop. They reflect on the origins, lessons, and future of a movement that’s always been too real to fade.What was the spark moment when NoizBoiz became more than just friends messing about?Me and Mucky have known each other since I was about 15 and he was 13. Before either of us did music, we were just big on sound — hip-hop, dancehall, jungle. We started writing parts here and there in school before grime even existed. At the time, it was all drum & bass and jungle. We went to a lot of those raves in Rotterdam — the DNB nights called ‘Illy Noiz’ — and when grime came along, it felt like a natural next step because we were already deep into garage and jungle. Once we heard Eski beats and Wiley’s productions, we just wanted to make that kind of sound ourselves. That’s how it started.How were you exposed to those early grime beats?Garage was big here — especially around 2001–2002 — with collectives like SPEADFREAX (SPDFRX) in Rotterdam, a clubnight showcasing UK Garage music. It started evolving into something darker, and that sound caught us. We had MTV Base for a short while, so that’s how we first saw So Solid Crew and More Fire Crew. Then came Limewire and Kazaa — old-school download platforms. We’d type in whatever names we found and download sets. One day we saw “Rinse” pop up, and that’s how we discovered Rinse FM. From there, we found Deja, Heat FM, and other pirate stations. That’s what really pulled us into grime.Was there a pirate radio scene in the Netherlands?Not really. There were underground parties, but nothing like the pirate culture in the UK. Hip-hop was around, but it wasn’t big — more underground. There were maybe one or two mainstream artists, but the pirate MC-and-DJ format wasn’t really a thing. We had illegal hip-hop parties and warehouse events, but not radio. Drum & bass, though, that was thriving. In Rotterdam, we had nights like Illy Noiz at Nighttown and Resistance at Waterfront. You could smoke in there, they’d play drum & bass, and show skateboarding videos on small screens. Me and Mucky were into graffiti and skating too — it all came from the same energy.That crossover of music, graffiti, and skating feels like part of the same culture.Exactly. It’s street energy. And even though I come from a Caribbean background, my parents didn’t play that kind of music — more soul and Surinamese tunes. My cousins brought dancehall tapes from Suriname, so I grew up on Super Cat and Shabba Ranks. The MC energy in that music was what connected me to grime later. It’s the same spirit.How did you both start making music? Did you have musical backgrounds?Yeah. My dad was a gospel singer, so there was always music in the house. I played piano as a kid. Mucky played saxophone and was always technical — if you gave him software or gear, he’d master it in three days. That curiosity drove him to start producing. We’d listen to beats and think, “How’s this made?” and then try to make our own versions.How would you describe the NoizBoiz sound today?It’s always been a blend. From our first album in 2008, we had grime, garage, dubstep, drum & bass — everything. That’s why people couldn’t box us in. We’d get booked for house raves, hip-hop festivals, school parties — anywhere with loud music. In the Netherlands back then, people didn’t know what grime was. They’d see a Black guy with a mic and assume hip-hop, or think it sounded like pop or house. But we just did our thing. Over time, we’d win people over — by the end of the set, they’d be like, “What is this? It’s mad!”Where has music taken you that you never expected?Everywhere, man. I once took 60 flights in one summer just for music. I’m sitting in a studio in Los Angeles right now because of NoizBoiz. We’ve toured, travelled, and connected through this sound. I’ve been to Suriname multiple times because of music — sometimes for my own shows, sometimes managing artists. Music’s given me everything.Tell us about the ‘NoizBoiz Presenteert: Zware Bassen, Zware Beats’ series and your 2025 release.The series started in 2010, originally inspired by an early member, Kariszma, who coined a name that summed up our sound — heavy basses, heavy beats. NoizBoiz Presenteert is a banner to showcase the spectrum we love — grime, garage, dubstep, drum & bass — not just our own tracks. The 2010 launch party sold out and really put us on the map; people were buying tickets to another main-room event just to get into ours. From there we kept the series moving — 2012, 2014, and now into 2025 — always pushing the sound and platforming likeminded producers and MCs across the Netherlands. Hayzee (now Southeast Hayes) from Zwart Licht was part of the ZBZB series too, alongside day-ones like Hazat and newer faces such as Nelcon.What collaborations only happened because of the music—like your big collab with Wiley?We met Wiley through a chain of shows and mutual friends. Years back we played a small Amsterdam festival where Skepta and JME were also booked. Backstage they told us, “You lot have proper grime—but you’re not even from England.” We stayed in touch. Later, at a Westerpark festival where Skepta performed with Maximum, Wiley was around; Skepta introduced us properly. Wiley said he loved Rotterdam and took my number—then actually pulled up. He ended up staying in town for about half a year. Mucky was constantly making beats; producers were sending riddims daily. We were spinning ideas in the kitchen when Wiley clocked one beat, left for Cyprus, called back five days later like, “I need that one.” He came back, he and Mucky made “Speakerbox”, then we cut our version “Fris” (NoizBoiz ft. Wiley). From there Wiley dropped “Boasty”, which blew up. All of that sprang from live shows, real conversations, and the music connecting first.Who’s been part of the journey—day-ones and new faces?Both. Our guys Hazat have been with us since the beginning. More recently we’ve pulled in younger talent like Nelcon—he told us our work influenced his style, and when we linked up we could tell he really knows his stuff. From the second installment we had producers like Curifex (dubstep/garage). When I’m back in Holland after ADE we’ve got a session planned with Styn. The aim is always to bridge generations and keep the ecosystem alive.You mentioned Styn — what’s the story there?Fun one: Don hosted a radio show back in the day and was the first person to play a Styn tune on air — Styn told us that recently. I’ve done an official remix for a track he produced with Brunzyn, and there’s a little reel on Instagram where I’m styled like him. It’s garage-leaning; full-circle moments like that are what keep it exciting.Your latest 101Barz session made noise. What were you trying to push there?We’ve done a few 101Barz sessions. The most recent one was about platforming the scene: bringing through Lost (Soultrash), Nelcon, and GGG, an original NoizBoiz member from way back — we even brought GGG to 101Barz ourselves. 101Barz reaches the youth; after it dropped, kids at my football club were like, “Sir, we saw you on 101!” It’s a powerful way to put grime and bass music to new ears.What are the biggest lessons from 20+ years — artistic and business-wise?Artistically: authenticity is everything. We once overthought an album (2014’s Oase) and promised ourselves never again — remember why we started. Live shows are our superpower, so we work with people who understand that. Business-wise: partner with teams who actually listen and get your vision. We’re with Mojo now on terms that suit us, and it’s a respectful, flexible relationship.What can people expect from the next run of shows?At ADE we’re doing more DJ-driven sets, and at Patta x Keep Hush we’ll add a live performance — energy high, a mix of new cuts and classics. We’re in LA wrapping a new project and aiming for festival shows next summer. Stay tuned — new music is loading, and we’ll be road-testing it soon.As the beat of Amsterdam Dance Event 2025 builds, Patta and Keep Hush return for the third time — and you know what they say: three’s the magic number. This year, the partnership levels up, uniting three of the city’s most forward-thinking collectives — Sankofa Archives, Mosaiko, and Studio Strip — for a night that goes far beyond your standard ADE rave.This is community in motion: collectives linking up, sounds colliding, and energy multiplying into something bigger than the sum of its parts. From live sets by NoizBoiz to stacked B2Bs, selectors, and special guests, it’s an all-Amsterdam celebration of sound system culture, experimentation, and underground connection.Tickets are live now — don’t sleep. Join the movement and secure your spot at Patta x Keep Hush, where the community takes centre stage.-

Get Familiar

-

-

What went down at Patta x Nike Air Max DN8 Marsaille

What went down at Patta x Nike Air Ma...

When Patta touches down, it’s never just an event — it’s a statement. For the Patta x Nike DN8 launch in Marseille, we brought that same energy to the south of France with a weekend that celebrated community, culture, and connection through motion.We kicked things off with a community run through the city — local crews, visiting runners, and Patta Fam all laced up to move as one. No medals, no finish lines — just rhythm, sweat, and unity on Marseille streets, powered by the DN8’s flow.As the sun dipped, we flipped the pace. The night belonged to the music — a club session that brought together Marseille’s finest selectors and international guests for a night that moved like the city itself: raw, unpredictable, and full of heat. Beats bounced off walls, basslines rolled like waves, and the DN8 spirit ran through every drop.All day long, the celebration continued live on air with a Oroko radio broadcast takeover, broadcasting from the heart of the city. DJs, artists, and local voices came together to share stories, sounds, and what it means to move with purpose — connecting scenes, bridging frequencies.Marseille showed us that when you move together, you move forward.-

What Went Down

-

-

Get Familiar: Pongo

Get Familiar: Pongo

Photography by Axel Joseph | Interview by Passion DzengaFrom the streets of Luanda to the global stage, Pongo has turned movement into meaning. Once known as “M’Pongo Love,” a name given to her by her father during her recovery, she has carried that strength into a career defined by resilience, rhythm, and reinvention. As one of the most distinctive voices in Kuduro, Pongo embodies the duality of survival and celebration — transforming her personal story into an unstoppable force of sound and identity.In this conversation, she reflects on her journey from the train stations of Lisbon to international fame with Buraka Som Sistema, the creation of the anthemic “Kalemba (Wegue Wegue),” and the lessons learned about ownership, artistry, and self-worth. Speaking candidly about healing, independence, and the evolution of Kuduro, Pongo reveals how she’s balancing her Angolan roots with a global vision — and why her mission now is to inspire a new generation to move, dream, and express themselves unapologetically.Your father nicknamed you M’Pongo Love during your recovery. Do you feel that name and the story behind it still echoes in your identity as Pongo today?Partly, yes. Today I also identify with the strength of the artist M’Pongo Love. She deeply inspires me — not only through her resilience, but through her independence. She even created her own record label later in her career, and that motivates me to keep working toward having my own label one day too.Can you take me back to the moment you first saw Denon Squad performing on the street? What did that spark inside you?At the time, I used to make that journey twice a week, and I was always curious to see Denon Squad performing at the train station. On my way to physiotherapy, they would be dancing and singing Kuduro, and from the very first time I saw them, something powerful awoke inside me — a strong sense of belonging and identity.When you first began dancing and rapping, did you see it as escape, empowerment, or both?Both. I was already dancing at family events — it was always a competition between the kids! I also took part in neighborhood dance battles back in Angola. When I moved to Portugal, I started rapping in my teenage years, so for me, it was all connected: an escape from the challenges of growing up, and a source of empowerment from the very beginning.At just 16, you went from performing with friends in the street to sharing stages with Buraka Som Sistema. What was that transition like for you?When I joined Denon Squad, I was just a dancer. I ended up participating in a song they were recording, and that track was later shared with Buraka Som Sistema. That’s how they reached out to me — and for me, it felt surreal. Everything happened so fast.“Kalemba (Wegue Wegue)” became a global hit almost overnight. Did you realize, when you wrote it, how much impact it would have?Honestly, no. The entire composition of Kalemba (Wegue Wegue) was deeply personal for me. It was rooted in my story — in the way my parents, as immigrants in Portugal, kept our Angolan culture alive in our daily lives. The global impact was something I only realized later. Seeing the song cross borders and connect people around the world was a huge surprise, but also a confirmation that when art comes from an honest place, it finds its way. Kalemba was exactly that — a spontaneous celebration that grew into something much bigger than I ever imagined.Leaving Buraka Som Sistema must have been difficult. Looking back, what lessons did that chapter teach you about ownership and self-worth in the music industry?I didn’t choose to leave Buraka — the group made that decision for me. And because of that, I decided not to return. It was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made. That project wasn’t just about music; it was a movement, a community, a family. Over time, though, I realized that even as we were breaking sonic and cultural boundaries, I already had a strong sense of control over my creative identity — especially within Kuduro. That experience taught me that if you don’t define your role and your value from the start, someone else will do it for you. Since then, I’ve become much more intentional about understanding contracts, royalties, and the business side of art. But most importantly, I learned that self-worth isn’t tied to the size of the platform or the volume of applause. Sometimes, stepping away is the most powerful thing you can do — especially when it means choosing yourself, your voice, and your future.Kuduro has often been misunderstood or pigeonholed in Europe. How do you describe it, and what makes it so powerful to you?For me, Kuduro is much more than a musical style — it’s an expression of resistance, energy, and identity. It was born on the streets of Angola as a form of liberation, driven by the Kazukuta and Hip-Hop cultural movement. Its force comes from both body and soul. What makes it powerful is its ability to bring people together — to turn pain into dance, and to tell stories that come from our African roots.Your work brings in influences from Angola, Portugal, and global club culture. How do you balance honoring tradition with pushing boundaries?For me, tradition and innovation are not opposites — they walk side by side and strengthen each other. Honoring tradition means keeping the spirit and truth of Kuduro alive, but it’s also about experimenting, mixing sounds, and taking that energy into new spaces.You often sing in Kimbundu and Portuguese. How important is it for you to weave language and cultural identity into your music?Language carries memory, history, and emotion. By weaving it into my music, I invite listeners into my cultural universe. It’s my way of saying that our languages belong in contemporary music — and that we can stay true to ourselves even when we’re speaking to the whole world.After everything you’ve lived through, do you see music more as a form of survival or a celebration?For me, music is both survival and celebration. It’s still my refuge during difficult times and gives me strength when I feel like giving up. But it’s also joy, freedom, and celebration. Each song is a way of honoring what I’ve been through while celebrating who I am and who I’m still becoming.Mental health and trauma are often taboo topics in immigrant communities. How have you learned to process yours, and does that healing appear in your songs?It’s true — talking about mental health and trauma is still taboo in many communities, not only among immigrants. In my case, I had to find the courage to look inward, to face my pain, and to transform it into art. Music became a space for healing. When I write and sing, I’m often processing those wounds, and I believe that energy reaches the people who listen.Winning the Music Moves Europe Talent Award in 2020 was huge. Did that feel like recognition not only for you, but for Kuduro as a whole?Winning that award was a huge milestone. It wasn’t just personal recognition — it felt like recognition for Kuduro and for Angolan culture. I was proud to represent that collective strength and show that our music belongs on the global stage.Your EPs Baia and Uwa felt like bold statements of independence. How do they differ in terms of your personal journey?Baia was a cry for independence — a moment where I affirmed my voice and said, “I have my own path.” Uwa is more mature and introspective; it speaks about healing, ancestry, and rebirth. Together, they trace my evolution — from liberation to deeper self-discovery and creative vision.Kuduro is now inspiring younger generations globally. Do you feel a responsibility to guide where it goes next?Yes, I do — and I carry that responsibility with love. Kuduro is a living movement, and seeing it inspire younger generations is beautiful. I want to help show that it can grow without losing its roots — that it can speak to the world while staying authentic. I see myself as a bridge between the past and the future, inspiring others to respect where Kuduro comes from while exploring where it can go.If a young Angolan girl living in Lisbon listens to your music, what do you hope she feels?I hope she feels seen and represented. I want her to know that her voice matters — that her origins are something to be proud of — and that she can achieve anything without ever having to apologize for who she is. I want her to feel pride, strength, and freedom, and to know that she belongs, just as she is.Finally — what’s next for Pongo? Where do you want this journey to take you in the coming years?What comes next is growth — exploring new sounds, collaborating with artists from different parts of the world, and bringing Kuduro to spaces it’s never reached before. I want this journey to be long and full of discovery. Most of all, I want to keep telling real stories — my own, those of my people, and those of the world — and continue inspiring others to do the same.Don’t miss it! During Amsterdam Dance Event, Pongo brings her explosive blend of Kuduro, Afrofunk, and global club energy to Paradiso for an unforgettable live show full of rhythm, power, and freedom. Expect pure adrenaline, unstoppable movement, and a performance as visually striking as it is emotional. Experience the voice of a new Kuduro generation live — get your tickets now for Pongo at Paradiso during ADE!-

Get Familiar

-

-

Get Familiar: Kekoto

Get Familiar: Kekoto

Interview by Passion DzengaNorthwest London’s own Kekoto, known musically as Keko, has steadily carved a lane at the crossroads of culture, experimentation, and self-made innovation. An artist, creative director, and self-described cultural innovator, he carries the dual identity of a grounded Londoner and a global-minded creator. From R&B and Gambian-Senegalese melodies in his childhood home to the late-night Channel U discoveries that shaped a generation, Keko’s sound is rooted in heritage yet driven by experimentation.Balancing raw emotion with cinematic vision, his evolution from the introspective in the meantime to the defiant 2L2Q (Too Legit to Quit) reflects both personal growth and perseverance through hardship. Across projects like Crimson and K-onenine, Keko fuses alternative rap with melody, texture, and storytelling—crafting immersive worlds as much as records.Through his creative umbrella Mismaf, he extends his artistry beyond music into visuals, fashion, and direction—building an ecosystem where every element speaks the same language of independence and innovation. Grounded in community and sharpened by honesty, Keko’s ethos is clear: live creatively, own your craft, and let the work speak louder than the hype.For people discovering you through now—who is Kekoto/Keko, and when do you use each?Kekoto/Keko are both me. I’m an artist, creative director, and cultural innovator. “Keko” is the music-side nickname—more informal, more personal. If someone uses “Kekoto,” they probably just found me. In short: Kekoto/Keko is a cultural innovator—overall, a wavy youth.You’re from Northwest London. How did NW shape your sound and stories?It shaped everything—sound, style, even how I carry myself. What I do connects worldwide—Amsterdam, Germany, Paris—but I know who I speak for and where I’m rooted. Northwest London is deep in the music and in me.Take us into your early musical moments. What was playing at home? First CDs? First discoveries?Born in ’98, the house was R&B and native sounds—Senegalese/Gambian music, jelis and kora traditions. My first rap memory is Nas—“I Can” really stuck with me. Discovery-wise, Channel U was huge. I’d stay up late for grime and UK garage—seeing people who looked and sounded like me, shooting videos where I lived, on TV. Mind-blowing.You also read a lot growing up—did that feed the ambition?Always. On the tube I’d read the music sections in the newspapers as well as all the magazines—Clash, NME, especially the award show write-ups. Even before I made music I thought, “I want to be at one of these. I want to win one of these.” That fueled a goal to do something culturally innovative the next generation can point back to.Press often mentions your smooth lyricism and melodic approach. Where does that come from?I’m a rap artist—alternative rap—but melodies pulled me early. R&B at home plus Senegalese/Gambian patterns are ingrained. Later I got into odd edits—people called it “trap,” but a lot of it was more dubstep/techno-adjacent SoundCloud energy. I like that experimental edge.When did you realize, “I can really do this”?2018. I booked my first studio—one hour, turned up 30 minutes late, spent 20 minutes hunting a beat. The producer said, “Punch something in.” I recorded my first released song in ten minutes. Hearing it back, I knew I could do this. Getting truly serious came around 2023 with in the meantime—the listening party, the turnout—then doing it bigger for 2L2Q at Peckham Audio. Watching the footage like, “All these people were here for me.” Since then we’ve done multiple headliner-style listening parties. It keeps building.Walk us through your creative process—what’s non-negotiable?The beat. If I don’t feel it, I’m onto the next—no matter who sent it. I love ethereal sounds that give goosebumps—close your eyes and see a world. I prefer beats being built live in the session. I’ll start writing, lay something, then punch in—very in-the-moment and experimental. A lot of first-thought honesty.Your music feels cinematic. If it were a film genre, what would it be?A thinker you rewatch for new interpretations—David Lynch vibes (Mulholland Drive), Eyes Wide Shut, The Matrix. Visually bold like Belly, Fallen Angels, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—colorful, stylish, still fun and gripping. Spike Lee’s stylization too.You’ve mentioned DIY and struggle shaping innovation. How so?Innovation comes from constraint. We weren’t born with silver spoons—so we live creatively because we have to. That resourcefulness is part of the culture and the art.Early on, did you tell people you were making music?No. I kept my head down and did the work. It leaked eventually—my private Insta linked to Facebook, aunties back home seeing it. But I moved quiet until the craft could speak.Your first tape, in the meantime—what did it prove to you?It captured a transition: where I was vs. where I knew I could go. I could complain about what I needed—or act. in the meantime asked, “While I’m heading to the version of me I see, what am I doing right now?” Sonically and visually, it’s a timestamp—busy artwork, real-life energy. It started as a “side mission” before a bigger album… then became the main mission. That happens a lot with me.What did listeners miss that you heard instantly on that record?People had notes on the mixes. I wanted a raw, authentic, slightly rugged sound—2L2Q doubled down on that: somehow polished yet rugged. We even lost stems on “2L2Q” with KBO and released the mix we had. It worked—good audio with texture. The point wasn’t clinical perfection; it was feeling.Moving into the next era—what was the goal for the sound?2L2Q is exactly what it says—Too Legit to Quit. 2024 was testing—trials nonstop. In hindsight it made me stronger, but living it wasn’t fun. The tape says: I didn’t come this far just to get this far. You hear it—I was writing on my worst days, speaking directly. It’s bigger than me.So in the meantime was discovery. What’s the arc after that?in the meantime was figuring it out. 2L2Q is: I’ve discovered it, and I’m here to say it. Crimson keeps that energy but is more curated—more world-building and artistic direction.Your release rhythm feels like 2000s mixtape culture—dropping between albums to show resilience. Why keep that pace?People grow up and move on, so from early you need to know who you’re speaking to. If they truly relate, time won’t break that bond. A lot of folks quit. Staying power matters, but only if you’ve got something real to say.Tell us about K-onenine—concept and how it came together.K-onenine is a collaboration between me, A19, and MV (producer). We locked in for a few months and suddenly had a tape. We sequenced it, got the cover right, tested it—Amsterdam trip, a pre-listening party where attendees got USBs with the tape—then the release party on drop day. The response made us double down. It could’ve stayed a side project while we worked on other things, but we said, “The world needs to hear this now.”Who are your core collaborators?Not exhaustive, but: producers nv, mannydubbs, Proton, A19, Kibo; creative team Melo (photographer/director), Detroit (artist), MS, Sam Swervo; Chinua (DJ); Retita (hair stylist); Cojo, Oscar—and family in Amsterdam too. So many people believe in this and make it happen. That’s another reason it’s “too legit to quit”—it’s bigger than me.Hip-hop has that “pull each other up” ethic—iron sharpening iron. Is that your circle?100%. My people won’t let me slack. If a song isn’t it, they’ll say it. That honesty keeps the bar high. I’m for bringing back a bit of gatekeeping—once someone proves themselves, cool, but standards matter. When bars drop, sub-genres get watered down.Let’s talk visuals—cover art and videos. How do you approach them, and where does Mismaf fit?I start with a rough concept that evolves. I don’t like text on covers—I want the image to tell the story and leave room for interpretation. Mismaf is my creative umbrella; clothing is one medium. I put all my creative work—music included—through Mismaf. Sometimes there’s joint venture distribution with labels, but it’s my house for ideas.Ownership keeps coming up. Why is it important to you?Ownership is key. Chasing hits for money kills passion. I keep it fresh—even if I have to switch process or environment. Whatever it takes.Off socials—when you’re not making music or building Mismaf—what keeps you inspired?Life. I’ll ditch the phone, end up in a bookstore, read something that sparks a whole Mismaf collection. My deepest, longest-lasting inspiration comes from living—not the phone.As the beat of Amsterdam Dance Event 2025 builds, Patta and Keep Hush return for the third time — and you know what they say: three’s the magic number. This year, the partnership levels up, uniting three of the city’s most forward-thinking collectives — Sankofa Archives, Mosaiko, and Studio Strip — for a night that goes far beyond your standard ADE rave. This is community in motion: collectives linking up, sounds colliding, and energy multiplying into something bigger than the sum of its parts.From live sets by NoizBoiz and Kekoto, to stacked B2Bs, selectors, and special guests, it’s an all-Amsterdam celebration of sound system culture, experimentation, and underground connection. Tickets are live now — don’t sleep. Join the movement and secure your spot at Patta x Keep Hush: where the community takes centre stage.-

Get Familiar

-

-

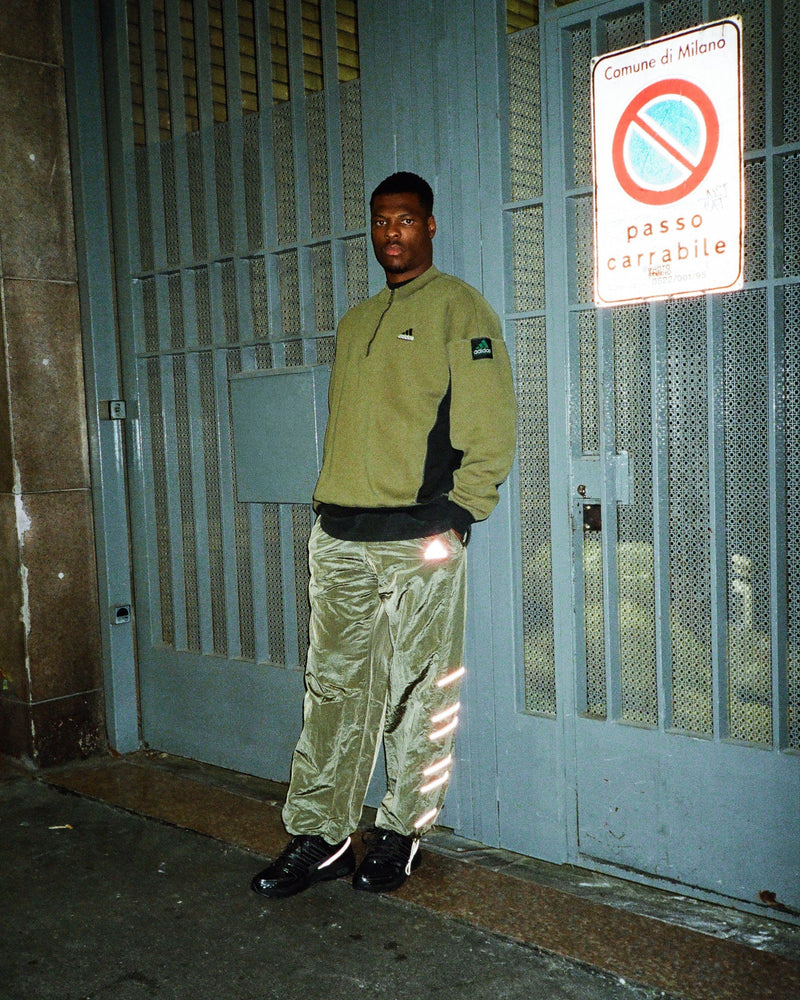

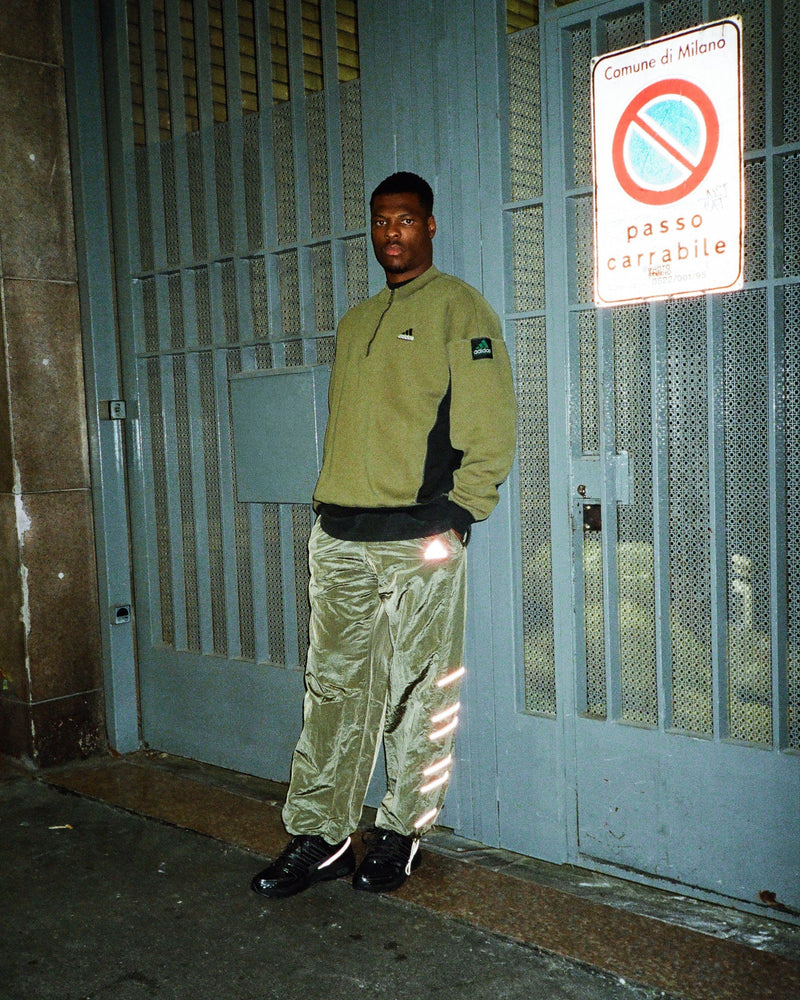

adidas EQT as seen by Patta

adidas EQT as seen by Patta

For 2025, adidas brings back one of its most iconic lines — EQT — with a heavy drop of footwear and apparel that nods to its legacy while looking straight ahead. To mark the moment, Denzel Dumfries fronts the campaign — an athlete whose energy and presence embody what EQT has always stood for: performance, purpose, and authenticity.When the first adidas Equipment line dropped in 1991, it changed the game. Built with no shortcuts, no gimmicks — just the best of the best. That same spirit still runs deep. From archive-inspired silhouettes to modern reworks like the EQT Prototype and EQT CSG, every piece carries the DNA of a range that once eclipsed everything around it — and still holds that power today.Over three decades later, EQT continues to define what it means to blend heritage with innovation. This isn’t just a comeback — it’s a reminder that true quality never fades.To celebrate the return, we’re keeping things rooted in the community with an in-store panel talk and DJ event at Patta Milan on October 15th, exploring one central question: What does club culture mean in Italy today — and especially in Milan?We’ll be joined by three panellists shaping nightlife both locally and internationally, including Lina Giselle, resident DJ at trrrmoto, who brings her insight on how the scene has evolved and what makes the Italian sound distinct. -

Tales from the Echobox 025

Tales from the Echobox 025

Interview by Monse Alvarado AlvarezFor the latest Tales From The Echobox, we sat down with Echobox resident, Kulumang at Café Warung PAS in Amsterdam Noord. We discuss his approach of constructing narratives through sounds, and his experience as part of Serumpun Kolektif. An Amsterdam-based collective that seeks to highlight the vitality and diversity of contemporary Indonesian and Southeast Asian creativity. Kulumang is the creator of the show, Suara Serumpun, a monthly program that explores the sounds of Nusantara. Keep reading to learn more about it as we prepare his next show. Remember to tune in on www.echobox.radioFor those who are not familiar with Serumpun Kolektif, could you briefly introduce the group and the projects you work on?The collective started out of a friend group. Today we’re about eleven people, and it came out of necessity. Most of us are Indonesian, mixed Indonesian or have Indonesian roots, and we live here in Amsterdam.We had a feeling that the representation of contemporary Indonesian culture, the voices of Indonesia today, were overshadowed in the Dutch context. As someone who is half Dutch, half Indonesian, and born in Indonesia, I missed the culture I knew from there. The discourse here was always overshadowed by the colonial past, Indonesia as a former colony, instead of focusing on what’s happening now and what people are saying today. Of course, it's important to talk about the complex history of Indonesia and the Netherlands, but we also want to share contemporary Indonesian culture: the creativity, the variety, and the talented people who often aren’t heard here.And what kind of projects does the collective represent? I read that Café Warung PAS was initiated by one of your members, Petra.Yes, that was done by Petra and it is now like a homebase for the collective. Food is such an important part of Indonesian culture, so we’re really happy that the restaurant became a place to connect.For example, on the 17th of August we celebrated Indonesian Independence Day. This was the third time we organized it. Four years ago, we were actually the first ones to celebrate outside of the embassy here in the Netherlands.Really?Yeah. And now, four or five other parties are organizing Independence Day events as well. Before, people didn’t really think it was possible to celebrate it here the way people do in Indonesia, like a King’s Day, with parties, games, fun, and of course, food. That was something we missed.Also, in the Netherlands, for a long time 17 August wasn’t even recognized as Indonesia’s Independence Day, from the Dutch perspective it was only two years later on the 27th of December, in 1949, after years of armed conflict and diplomatic negotiations. But in recent years, there’s been more discussion, remembrance days, and historical conversations that hadn’t been spoken about before. That’s important.After one year of hosting your Echobox show Suara Serumpun, can you walk us through your creative process, including how you choose and invite guests?Suara Serumpun is really an extension of the collective. It’s not only about Indonesia but also about Nusantara, a pre-colonial context for the broader maritime Southeast Asian region, including parts of Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines. Culture isn’t defined by borders, so it feels natural to also play music connected culturally but from different countries.My creative process starts with curating music from the region. I discover new scenes, often from Indonesia, because that is my starting point, but also I started broadening out to Malaysia, for example. For example, we had a guest, rEmPiT g0dDe$$, a Malaysian artist, who came here and played a live set. Through her I learned a lot about music from other areas of Nusantara.We’ve had both live sets and pre-recorded ones. Some guests came to the studio. We had two live sets from Xin Lie and rEmPiT g0dDe$$ while she was performing at Rewire festival. While others connected with us remotely, like the set from Xin Lie that we broadcast as a pre-recorded set. I also try to include local guests from Amsterdam to add their perspective.The guest lineup is not random, it depends on timing, connections, and opportunities.The shows I play, though, follow a more cinematic kind of way. I try to create storytelling through sound, with emotional qualities and field recordings to make it flow. My aim is to capture the dense, humid mysticism that drifts through the Nusantara atmosphere.It can move from slow to fast, ambient to energetic and make it dynamic. I also tend to push toward the experimental side and the different scenes, because I think that’s where a lot of amazing, lesser-known sounds come from. I want to highlight those voices. At the same time, I’m aware that the curation also reflects my own taste, and I sometimes question how much space my taste should take up. But I think it’s important to find a balance to represent the culture.How do you engage in dialogue with the diaspora through the show? Has it sparked new projects, collaborations, or connections in Amsterdam and abroad?Yes, definitely. For example, through the show we connected with Half East Records, a collective in London that focuses on Southeast and East Asian music. They came here for Independence Day, which created a new link between us. Beyond these international ties, the show also sparked local initiatives, like Raung. Our first edition took place in 2024 at the Sun Studios in Rotterdam, where we invited Kuntari, a two-man band from Indonesia, to close their European tour. By coincidence, on 6 September we have an event at Felix Meritis, where they’ll also open their next tour. These kinds of connections keep growing.We also bring together traditional and experimental perspectives in music. For example, the Raung event at Murmur featured derozan, Mangruv, and Bintang Manira. We explored Indonesian tonal scales and percussion rhythms, blending them with more contemporary, experimental approaches. In this way, the show functions as a hub, connecting local and international artists and helping build a network of culture and creativity.That’s beautiful. Okay, and what can we look forward to in your next show? Could you give us a small sneak peek?For the one-year anniversary, I want to create a compilation of my favorite tracks from the past year, something that really represents the spirit of the show. For the future, I’d like to include more guests, go deeper conceptually, but still keep the spontaneity.Nice. So after a year of experimenting, you feel you’ve found the basics of what you want, and now you’re ready to expand.Exactly, I know what I like, what works, and what I want to develop further. The show really works as a meeting point, a place where artists can connect with each other and with the local scene. I hope it helps build a stronger network with like-mind artists around Indonesian and Southeast Asian culture.Tune in to Echobox - broadcasting from below sea level every week, Wednesday until Saturday. -

Get Familiar: Black Sherif

Get Familiar: Black Sherif