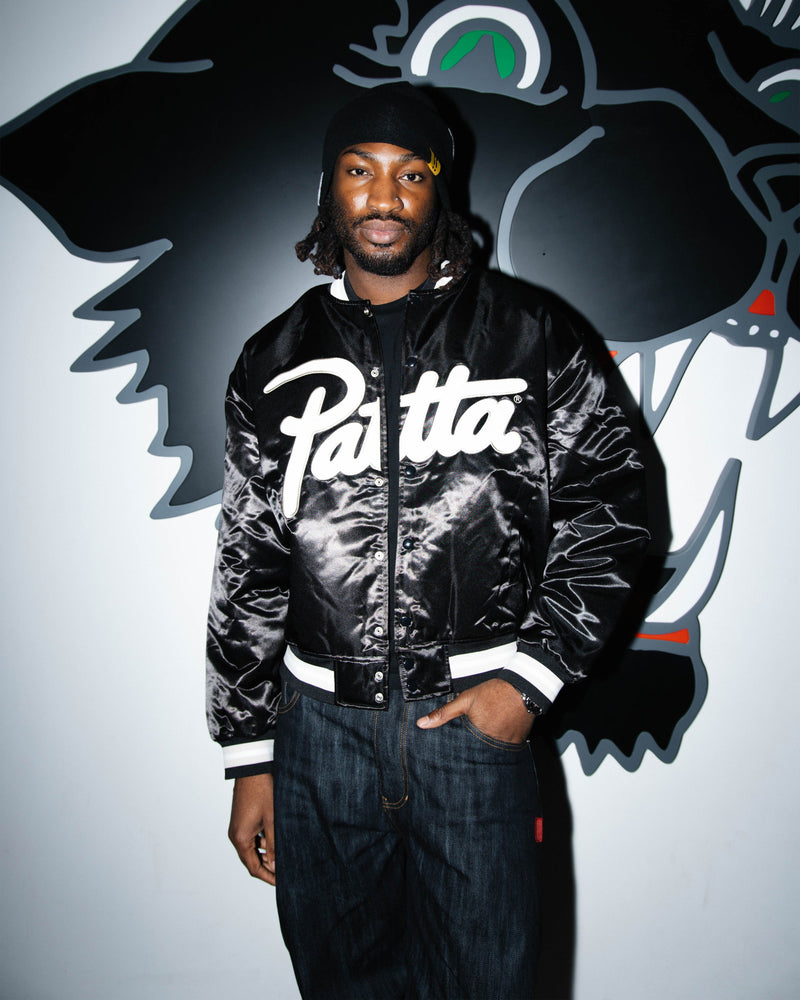

Get Familiar: Black Sherif

Interview by Passion Dzenga | Photography by Akadre Studio | Styling by Sonia Ihuoma

If you haven’t already tapped into the world of Black Sherif, now’s the time to get familiar. The Ghanaian genre-bender has come a long way since his First Sermon days, evolving from a hometown hero into a global voice with a message rooted in resilience, spirit, and raw emotion. With a sound that blurs the lines between drill, reggae, highlife, and rap—and a style just as genre-defying—Blacko is the kind of artist who makes you feel something, even if you don’t understand the language.

It’s been a busy year for the 23-year-old, whose real name is Mohammed Ismail Sherif. We spoke days before the release of his sophomore album Iron Boy, and the start of an arena tour across the US and UK. Sherif is entering his Iron Boy era with the quiet confidence of someone who’s lived, learned, and levelled up. He’s got love for his roots, love for the journey, and love for the people who see power in vulnerability—because for Black Sherif, that’s the real flex. We caught up with him to talk about patience, performances, personal growth, and the power of staying true to your source. Let’s get into it.

You’ve come a long way since your debut album. How do you reflect on your growth as an artist? How have you changed over time?

It’s been quite a journey—from The First Sermon to where I am now, preparing to drop my sophomore album. A lot has changed, especially in terms of how the world receives me and how the business works. But one thing that hasn’t changed is where my creativity comes from. The source remains the same. What has changed is me—I’ve grown. I’ve learned patience, and I’ve learned acceptance. Two or three years ago, things that happen to me now would've broken me. Today, I handle them with a different mindset. I respect the journey. As kids, we think success will come instantly—we write goals in our notes and expect them to happen on our timeline. But life teaches you patience.

Patience really does sound like the defining theme of your journey. Would you say that’s the biggest lesson so far?

Absolutely. Patience. This album, for instance, was supposed to drop eight months ago, but life happened. If I didn’t have patience, I would’ve crashed out. Learning to sit back, be part of a team, and let things unfold—that’s been everything.

Your sound is a unique mix of drill, rap, reggae, and highlife. How did you develop this blend? And what role do your Ghanaian roots play in that?

I don’t think I’ve ever said this before, but confusion helped me find my sound. I know how to do so many things, and I used to judge myself a lot—I'd write something and wish it sounded like reggae or something else. But then I let go. I stopped fighting the flow and started letting whatever came out, come out. The result is this unique mix. It’s not forced. It’s just who I am and what I’ve been exposed to—from Ghanaian music to Caribbean influences.

Highlife is such a traditional Ghanaian genre. How does it find its way into your music, especially when you’re blending so many Western sounds?

I even get surprised sometimes. I’ll be working with my in-house producer, Joker, and he’ll make these futuristic beats—but the rhythms, man, they just scream highlife. It’s not about language or lyrics. It’s in the rhythm, the melodies. And somehow, that same beat my Jamaican friends will hear and say, "This sounds Caribbean!" It’s wild.

Different things, but especially my mom. I remember being 10; that was the last time I was home with her. And the music that shaped me came from those early years. My dad came back from Greece when I was eight and introduced me to Don Carlos. “Harvest Time” was the first reggae song I learned. That shaped my idea of what music and art should be. Also, I still have friends from when I was six or seven; we’re still close, some of us even work together now. Those relationships keep me grounded.

You’re known for being vulnerable in your music. How do you manage that vulnerability while still showing strength and power in your art?

I find power in being vulnerable. Not everyone can do that. I see vulnerability as a superpower. There are so many people in the world who can’t speak or express what they’re feeling—but I can. And I have a space to do it through music.

You’ve worked with big names—Burna Boy, Vic Mensa, Mabel, Fireboy DML. What do you look for in a collaborator, and how do those collabs shape your sound?

Funny enough, I don’t think I’ve fully entered my collaborative phase yet. Most of the songs I’ve done came from relationships—someone sent me a track, and I vibed with it. But after this album, I want to travel, sit with artists, connect spiritually, and create. To me, music is spiritual. A perfect collaboration is when everyone’s spirit aligns on a track. That’s the kind of collab I’m chasing.

What sort of themes, sound, and your evolution as an artist on this second album?

It’s more elevated. Some of the beliefs I had two or three years ago—I’m challenging them now. I’ve found new ways to be personal and vulnerable. There’s a song called One that talks about something that happened to my father last year that changed everything in my family. It’s a spiritual album. You’ll have to listen to it to feel what I’m saying.

The album is called Iron Boy. What does that title mean to you?

The title is layered. First, it’s a tribute to a highlife legend from where I’m from—Iron Boy was his nickname. But also, "iron" represents being tough. The stuff I’ve been through recently? If it had happened three years ago, I would’ve stopped making music. But now, I’m iron. I’ve become that.

You’ve been called the voice of the Ghanaian youth. How do you carry that responsibility, and how do you reflect your community’s struggles in your work?

I've learned we all fight the system in different ways. For me, music is how I respond. I’m honest in how I reflect what’s around me. Where I’m from—Zongos—you don’t often see guys being this vulnerable. They’ll say, “Being soft gets you nowhere.” But I say it anyway. And that gives me power.

You mentioned a track called “Victory Song”, where you open up about crying in a hotel in London. Why was that moment important to share?

Because no one talks about that part of success. People see you on stage or travelling, but they don’t see the moments when the noise fades, and you’re alone with your thoughts. That moment reminded me that I’m still that kid from back home, feeling things deeply. I want people to hear that. That’s the kind of artist I want to be.

You’ve played massive shows—MOBOs, Wireless Festival, City Splash. What’s that experience like, and what stands out to you?

Every time I get on stage outside of Ghana, I tell myself, “Nobody here knows me. I’m here to sell them something I believe in.” At Wireless, the sound was so good I forgot I was performing to a huge crowd. It felt like a rehearsal. I just wanted two hours to sing.

What makes a great performance to you?

There are some things about performing that you have to learn, even if you're born with talent. When I watch people like Kendrick Lamar, their performances feel like an emotional roller coaster. Some songs don’t need dancing; they just need to be felt. You get more from watching the artist express it through gestures and facial expressions. I love all of that because I don’t think I’m a good speaker, but I’m super talented in nonverbal communication. That’s why I believe I’m one of the best performers from where I’m from.

You mentioned Kendrick. Are you aiming for a stage show that feels more like a play or theatre performance than just a concert?

Yeah. It’s more than just turning up. It’s about creating an experience. Like theatre, with costumes and pacing.

You’re considered one of the best-dressed men from Ghana. What sparked your interest in fashion?

It came from when I was young. My whole style started in a woman’s closet—my auntie's. When my mom left for Greece, I stayed with my auntie, and she had all kinds of stylish stuff. I’d sneak into her things, steal belts, and glasses. That’s when I got into appearances. I also tried different hairstyles, like one called “backbone,” and got beaten for it because it was too bold for where I was living. I’ve always been chasing freedom to dress how I want.

Did your mom’s background as a seamstress influence your fashion sense?

Definitely. I used to sew my buttons for school. Even in high school, I’d alter my clothes because I couldn’t afford a tailor. If I didn’t like something about a shirt or a pair of sneakers, I’d cut it and make it my own.

Last September, you walked for Labrum at London Fashion Week. What’s your relationship with high fashion?

I’m just getting into it. As a teenager, I couldn’t afford real designer clothes, so I wore replicas. But now, I get these things as gifts, and I feel like I have a fashion dream that will come true. After walking for Labrum, people told me I was natural at it. I thought I didn’t do a great job, but the reactions were strong. I’m still figuring out my way in fashion, but I believe in it.

How do you see your style connecting with your music?

Iron Boy is a supernatural being, and how he looks shouldn’t be relatable. The music and visuals are all extensions of each other. How I sing, how I dress, how I look—it’s about making people feel something, even if they don’t understand the words.

Tell us about your music video for the song “So It Goes” with Fireboy DML.

I loved the styling. I didn’t style Fireboy, but I was involved in my own styling. Some of the looks feel like video game characters. When I was a kid, I was really into gaming—GTA, Winning Eleven, and Sega. I don’t play as much now, even though I have a PS5, but those inspirations still show in my visuals.

What’s the concept of the music video?

It’s like a greeting from abroad. The character is on his way to war, like a traveller sending a postcard to a lover. You see him on a horse, surrounded by dead men—it’s poetic and emotional.

As a Ghanaian artist gaining international recognition, how important is it to remain rooted in your language and culture while appealing to a global audience?

I think my music speaks globally, even in a different language. Some people in Ghana don’t get what I’m saying, and people abroad do—emotionally. Emotions and melodies are universal languages. I’m still learning how to reach everyone, but I believe in the power of feelings.

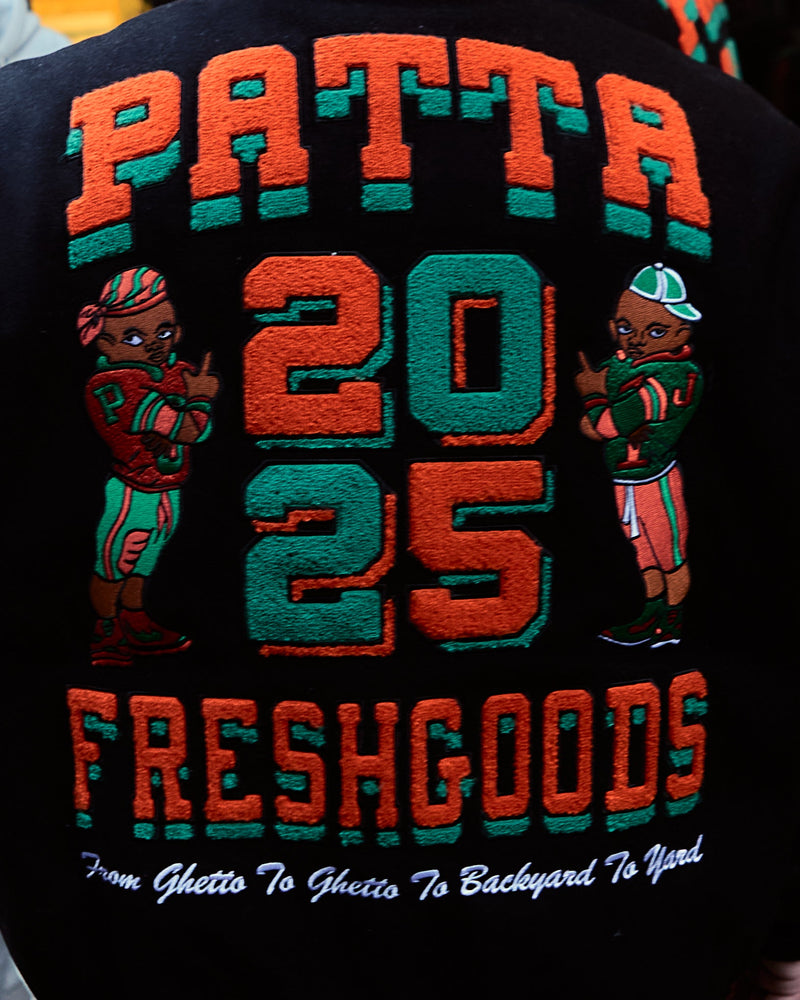

Find out more about Patta and the world around us through the Patta Magazine Volume 5, which is available now only at Patta Chapter stores in Amsterdam, London, Milan and Lagos.